The Source of the Ganges

I was the first to rise in the room full of Europeans, and set out before sunrise for Gomoukh, the source of the Ganges. As the sun climbed over the peaks to the east, Mount Shivling, a magnificent pyramid of granite and snow, refracted the earliest rays of light above Gomoukh glacier. Glittering in the morning glow, I was irresistibly drawn to the peak and my mind was unable to focus as I scrambled over the rocks separating me from the source of India’s holiest river. As I arrived at my destination, I was lifted higher and higher as I entered an ice palace sculpted by time and nature. The effect of the altitude, no doubt, contributed to my euphoria, and by the time I reached the river’s source I was soaring.

If heaven and earth had a meeting point, I was sure this was it. I had reached the source of the Ganges, the wellspring of the Hindu faith, and I soaked up its sanctity.

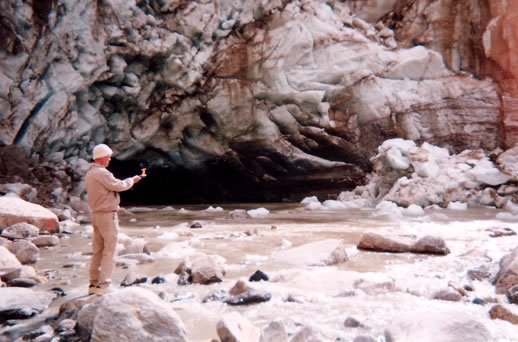

Alone amidst the pinnacles and silver-blue stream that emerged from an oval opening at the glacier’s base, I reveled in a transcendent mood. Seated on a boulder, I scanned the escarpments overhead. The amphitheater of rock and ice inspired reverence. If heaven and earth had a meeting point, I was sure this was it. I had reached the source of the Ganges, the wellspring of the Hindu faith, and I soaked up its sanctity. I thought about plunging into the freezing waters for the ultimate holy bath, but my rapture was short-lived when a boulder tumbled off a lofty crag and came crashing to the ground a few feet away. The thunderous concussion echoed from all sides, and my relaxed reverie was short-circuited. Startled by the displaced rock that had nearly crushed me, I moved closer to the sapphire stream to watch the chunks of ice as they floated past. I reached down to test the water and realized the foolishness of my plan for a bath. As I peered into the oval opening called Gomoukh at the base of the glacier, a massive block of ice broke off and plunged into the stream, sending a wave washing over my shoes. The pristine atmosphere was unpredictable, and my thoughts reflected that uncertainty. After christening myself with the holy water, I retreated.

As I climbed out of the glacier region, the gnawing emptiness in my stomach begged attention. I had not eaten a proper meal for thirty-six hours and was beginning to question the wisdom of approximating a mendicant’s life, if only for a day. As I retraced my steps to Bhojbasa, suddenly, out of nowhere, a sadhu appeared on a rock above me wearing nothing but a loincloth. His matted hair, beard, and nakedness gave him the appearance of a madman as he stood there on the boulder waving his arms at me wildly. But when I drew close enough to see his eyes, I knew he was anything but mad. His face was serene; his eyes clear like glacial pools. He gestured for me to join him in his hut and I followed him into his rough abode. He didn’t speak, but motioned for me to sit near the fire. Silence seemed to go with the territory.

His slender hands moved efficiently as he prepared tea and leafy greens. After eating, we sat for a time, enjoying one another’s silent company. The sadhu had wrapped himself in a coarse blanket that gave him a prehistoric look, but there was nothing primitive about his crystalline eyes. I felt an affinity with this kind soul who had shared his simple meal with me, and as I departed I bowed to him and placed the coins in my pocket on the stone altar outside before setting out for Gangotri. Years later, while browsing in a Delhi bookstore, I came upon some pictures of a Himalayan yogi in a coffee table publication by an Italian photographer. When I looked more closely I recognized the ascetic who had fed me at Gomoukh. His name was Swami Bhalawan and he was a Hatha yogi.